Aquatic grasses are a vital part of the water world

Life in most waterways depends on the survival of underwater grasses, which have been imperiled by pollution, lack of sunlight, dredging and development.

The temptation may be strong to make the shorelines of rivers, such as the St. Johns River, feel more like a sandy-bottomed lake. Underwater grasses feel squishy underfoot, and one might be a bit jumpy if a stringy plant brushes an ankle or leg.

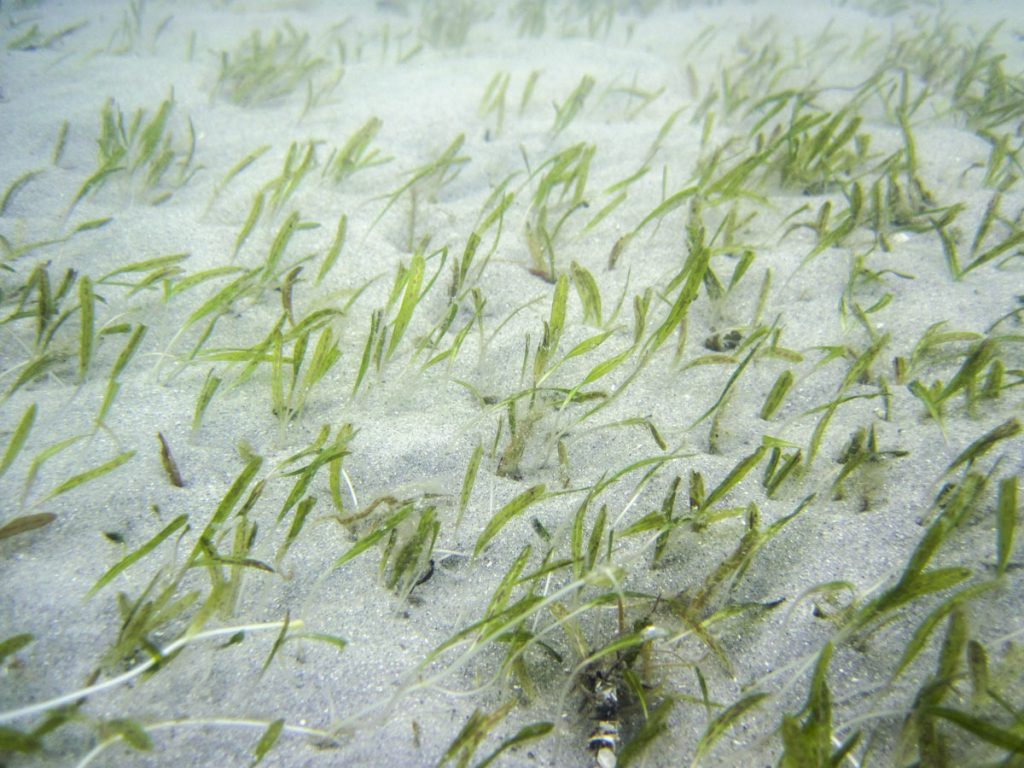

But when underwater grasses are removed or destroyed, a vital life-giving element of a waterway is taken away. A closer look underwater reveals a thriving micro-community.

The 310-mile-long St. Johns River is home to many plant species and marine animals — manatees, many types of fish, crabs, shrimp and other shellfish, river otters, waterfowl, and alligators and other reptiles.

Underwater plants here and in other waterways are food for some animals and nurseries for others. They act as surfaces for organisms — snails, algae and insects — to hold on to.

Submersed vegetation is also necessary because it adds dissolved oxygen to the water so aquatic animals can breathe. Without aquatic plants, the St. Johns River would not be as full of life as it is today.

Threatened grasses

Sixty seagrass species are found throughout the world. Of the many types of seagrass found within the St. Johns River Water Management District’s 18-county service area, one type of seagrass became a threatened species in the late 1990s under the Endangered Species Act — the first seagrass to be listed under the act.

Johnson’s seagrass (Halophila johnsonii) is found nowhere in the world except in the Indian River Lagoon, at the District’s southern end. Its roots help stabilize sediments, and its blades provide shelter for invertebrates (small spineless animals) and small fish. The grass also produces food for lagoon marine animals and microorganisms. But it is vulnerable to disturbance and is unable to colonize new areas, as no male flowers and thus no seeds have ever been found for the species.

By mapping seagrasses in the lagoon and other waterways, scientists can measure a waterway’s health by monitoring plant distribution and abundance from year to year.

Grasses indicate waterway health

In the lower St. Johns River, the most common plants found are eelgrass or tapegrass (Vallisneria americana), water naiad (Najas guadalupensis), and widgeon grass (Ruppia maritima), which is a salt-tolerant grass.

Information about underwater grasses is a critical tool in determining the river’s health, and the river’s water quality must be maintained at a level that supports the growth of underwater grasses.

Monitoring grass beds

District staff regularly collect scientific data about aquatic grass beds in the St. Johns River and the Indian River Lagoon.

This allows researchers to assess characteristics and differences in grass beds at locations throughout the District, and detect changes that occur only in certain areas.