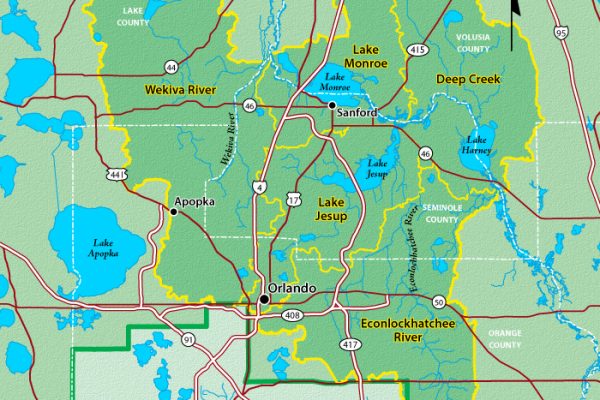

The Middle St. Johns River Basin in central Florida is a highly urbanized area that encompasses the watersheds of five major sources to the St. Johns River, extending more than 1,200 square miles. Each of the watersheds is unique and has characteristics that require variable and adaptive approaches when addressing water resource issues. The basin extends from the Econlockhatchee River in Osceola, Orange and Seminole counties northward into Lake and Volusia counties.

The St. Johns River Water Management District works to preserve those areas of the middle basin still in good condition and to restore those areas that have degraded over the years. The District’s ongoing work includes implementation of selected environmental restoration projects, monitoring, modeling, and diagnostics and analysis. Information gathered in the course of the District’s work is used to design facilities needed to extract phosphorus from these waterbodies.

The District and its numerous partners in the region have had many accomplishments, including expanding water quality modeling, diagnostics and compliance; developing total maximum daily loads (TMDLs); pollutant load reduction goals (PLRGs) and basin management action plans (BMAPs) to address water quality impairments; prioritizing stormwater retrofit programs for older developments; implementing erosion control projects and various water quality improvements throughout the basin; developing plans for subbasins that address the specific needs of the watershed; investigating land development rule changes to improve watershed protection; addressing flooding; and preserving environmentally sensitive land.

History of the Middle St. Johns River Basin

Life in central Florida has centered around its many waterways for hundreds of years. When Native Americans lived along the shores of the St. Johns River, it provided them with food and transportation. As European settlers moved to the wilds of Florida, the area’s waterways served as a route for commerce, with paddlewheel boats bringing tourists to the center of the state and carrying away citrus and other agricultural products grown on the river’s rich floodplain.

Even today, central Florida is known for its lakes, creeks, streams and rivers. Here, many find the natural beauty that leads them to adventure hiking in the centuries old woods, viewing the many birds and animals that live here, or paddling a canoe along a lazy waterway.

Like other areas of Florida, waterways in central Florida have been degraded over the years by stormwater runoff, discharges from agricultural and dairy areas and by wastewater treatment plants. Excess pollutants and sediments in stormwater runoff and other discharges can fuel the growth of algae. In some basin waterbodies, the natural flow of water has been altered for roads, flood control, aesthetics, erosion control and water level maintenance. These alterations limit the ability of the waterways to naturally cleanse themselves. In addition, the basin is highly urbanized with limited land available for restoration projects.

In 2000, the Governing Board of the St. Johns River Water Management District proposed the middle basin as a Surface Water Improvement and Management (SWIM) program to coordinate individual project areas into a regional framework.

The District’s partners in these efforts include the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), the Florida Department of Transportation, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers; Lake, Orange, Seminole and Volusia counties; the cities of Altamonte Springs, Casselberry, DeBary, Deltona, Eatonville, Edgewood, Lake Helen, Lake Mary, Longwood, Maitland, Orlando, Oviedo, Sanford, Winter Park and Winter Springs; the Florida Audubon Society; Orange Audubon; Friends of the Wekiva; Friends of Lake Jesup; and The Nature Conservancy.

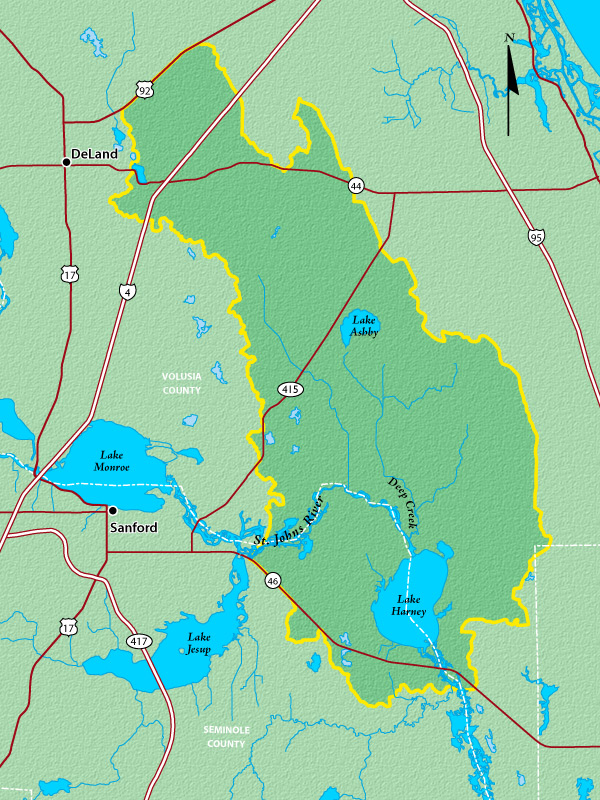

Deep Creek

Deep Creek is in portions of southern Volusia and northeastern Seminole counties, covering almost 274 square miles. Deep Creek provides a connection to the St. Johns River for Lake Ashby in Volusia County. Another major feature is Lake Harney, which is actually a widened section of the St. Johns River, with the river flowing into and out of Lake Harney. Lake Harney is a shallow lake, and is just one of the two lakes that form within the St. Johns River and are located within the middle basin — the other is Lake Monroe located further downstream.

Though significant areas are currently undeveloped in this basin, some residents experience flooding because structures were built in the 100‑year floodplain before regulations were established that govern construction in wetlands and low-lying areas. Through a variety of projects, the District and its partners have purchased environmentally sensitive land and enhanced wetlands and floodplains, preserved habitat for scrub jays and other wildlife, and are encouraging large landowners to conserve property as “conservation corridors.”

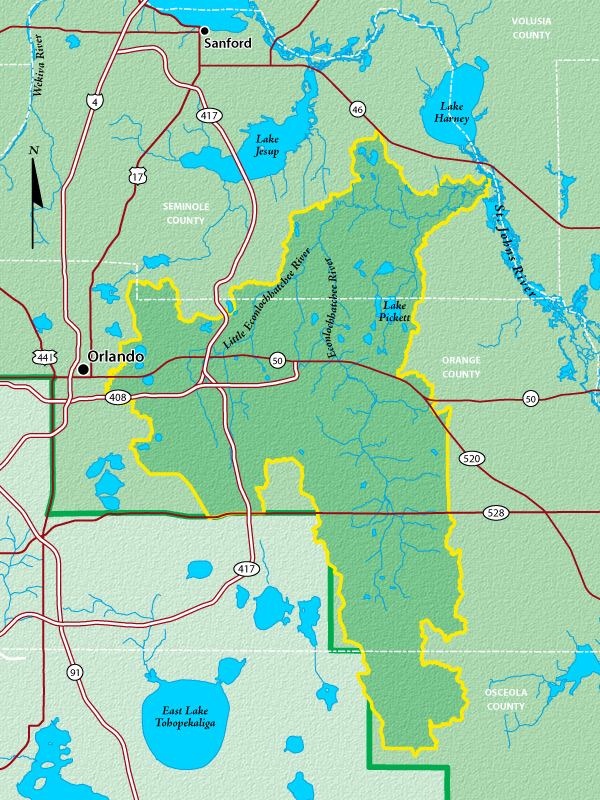

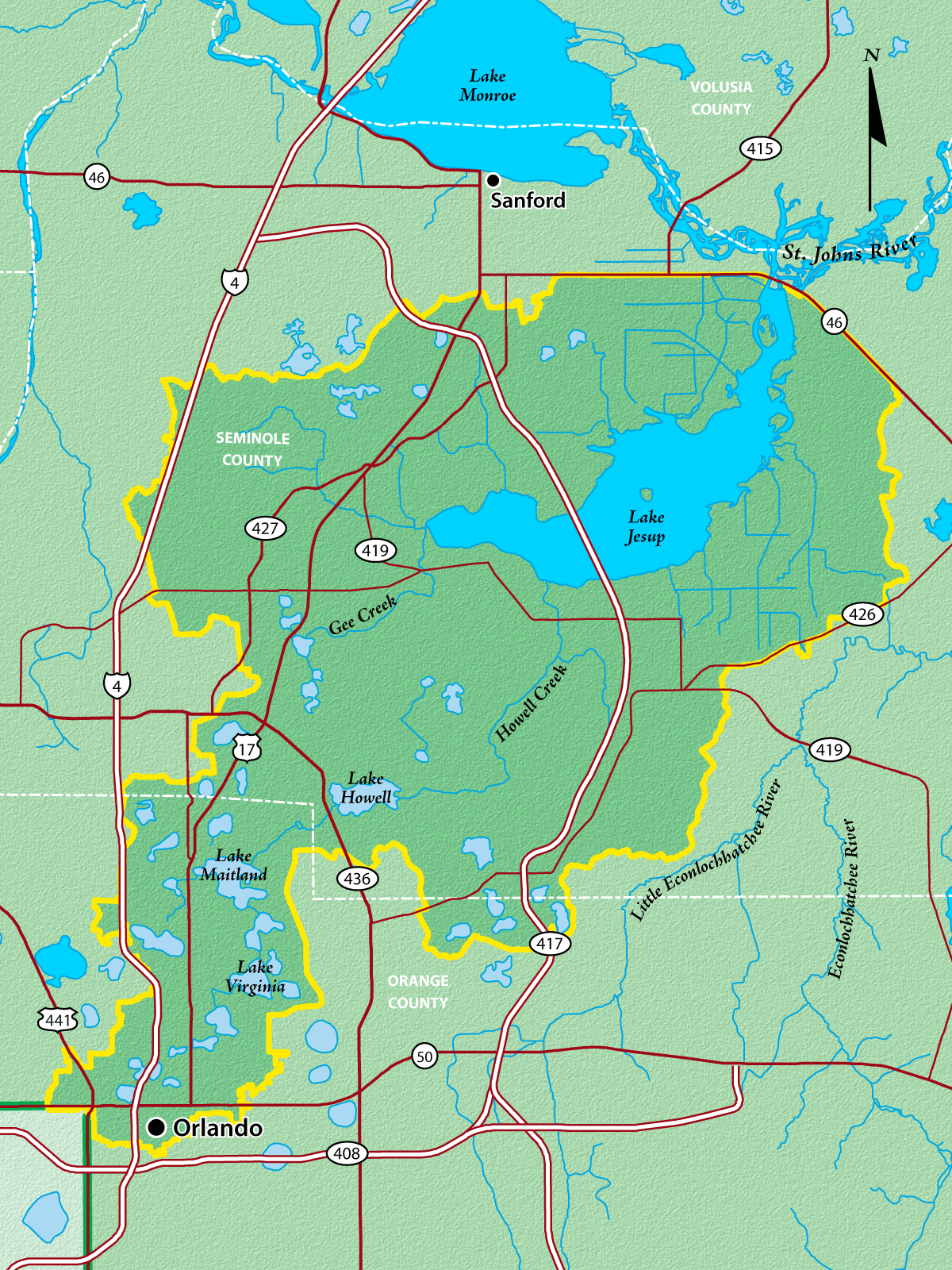

Econlockhatchee River

The Econlockhatchee River is a blackwater river located in Osceola, Orange and Seminole counties that is designated as an Outstanding Florida Water. The river is the second largest tributary to the St. Johns River, and includes a watershed area of 173,143 acres. Most of the development in the Econlockhatchee’s watershed began after the state’s water management districts put stormwater management rules in place. The area around the Little Econlockhatchee River, a tributary of the Econlockhatchee, was developed prior to stormwater management rules and faces many water quality challenges. Much of the natural river’s floodplain was filled and paved, and many miles of the Little Econ River have been channelized, creating a network of ditches that convey runoff from metro Orlando.

Local governments have worked to develop master plans to address water quality, flooding and water resource improvement issues. Because wetlands abutting the Econlockhatchee River and its tributaries support an abundance and diversity of aquatic and wetland-dependent wildlife, special regulatory criteria are now in place to require stringent stormwater treatment and other measures, including riparian protection to protect the river. Local governments and state agencies have purchased parcels along the Econlockhatchee River corridor to preserve some of the undeveloped land along the river.

Lake Jesup

Lake Jesup is a large, shallow lake in Seminole County. Its floodplain covers approximately 16,000 acres. Lake Jesup was once attracted thousands of recreational boaters and anglers each year. Water quality in Lake Jesup degraded over decades due to historic wastewater discharges, nutrient runoff from agricultural and urban development activities in its watershed and the lake’s relatively low flushing rate. While connected to the St. Johns River, the river does not naturally flow through the lake, resulting in excessive growth of algae.

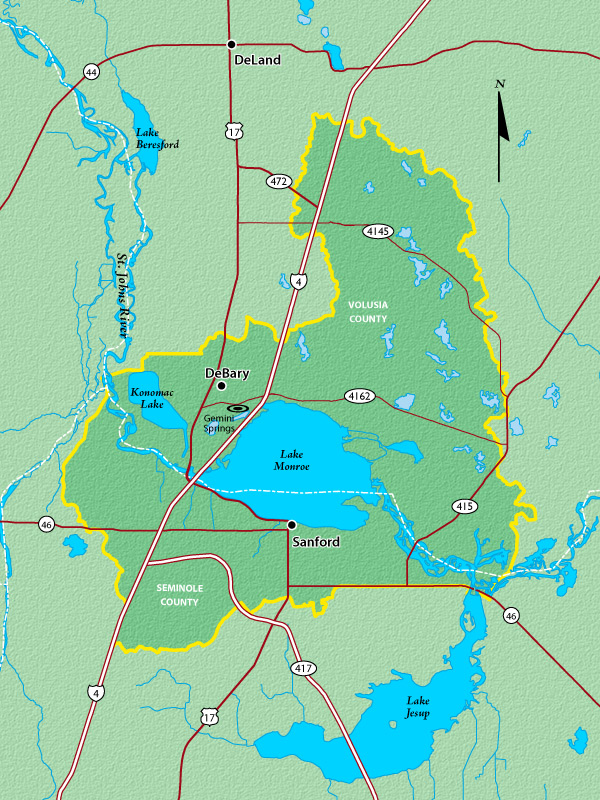

Lake Monroe

Lake Monroe is about 9,400 acres in size and is a shallow, wide area of the St. Johns River. Significant development has impacted the wetlands and waterways of this basin over the years, such as the Interstate 4 corridor and the development in the cities of Sanford, Lake Mary, DeBary and Deltona.

High levels of phosphorus from lawns and farming, untreated stormwater runoff from areas developed prior to stormwater regulations and wastewater plant discharges in the past led to the lake’s water quality degradation. Flooding has also occurred around the lake in the adjoining areas that drain poorly and in areas immediately along the shoreline.

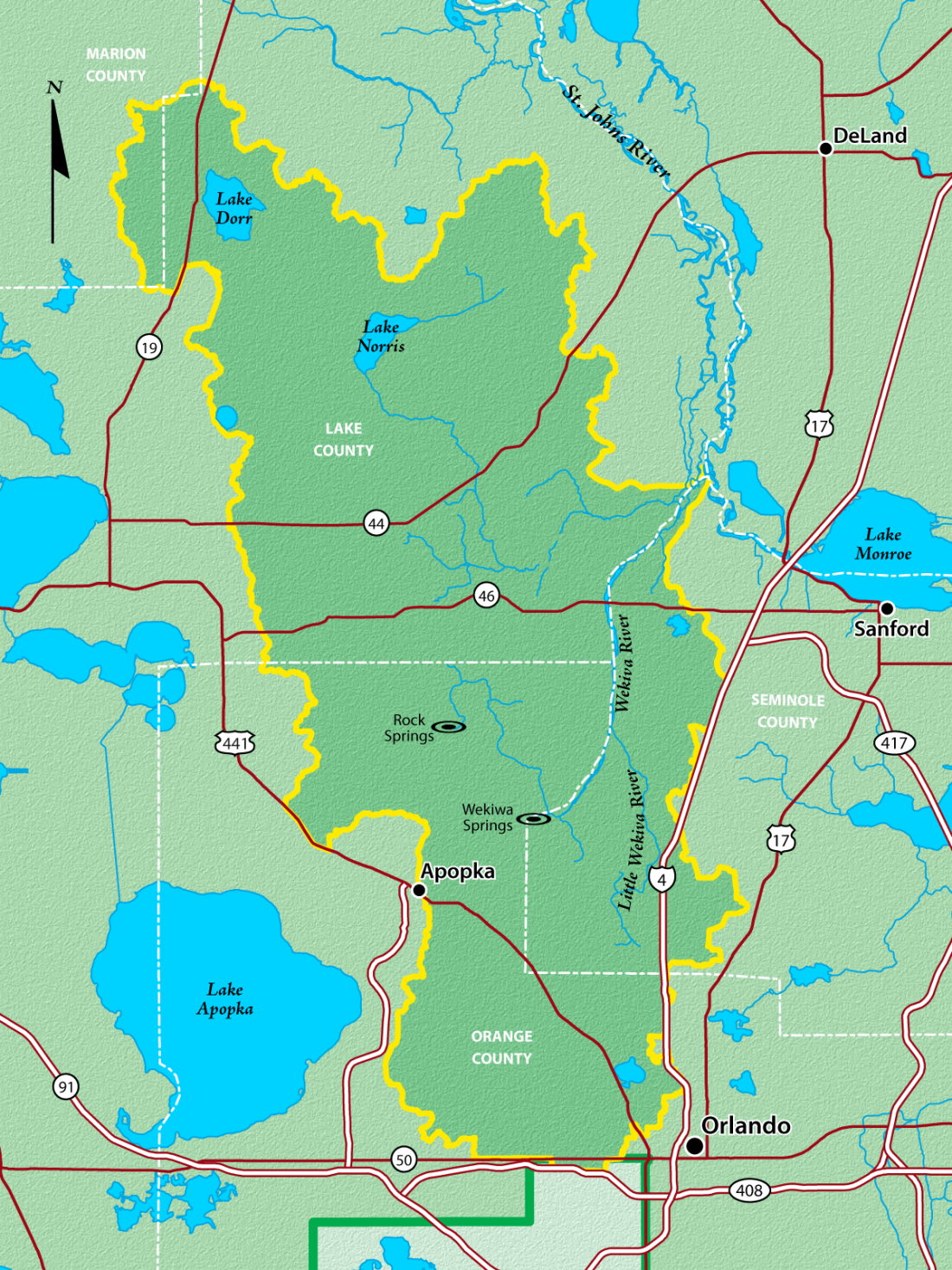

Wekiva and Little Wekiva Rivers

The Wekiva River system includes many unique attributes. The flow of the Wekiva River originates from a combination of springs and surface drainage from the region. The Wekiva River system in Orange, Seminole and Lake counties includes the main stem of the Wekiva River, three main tributaries (Rock Springs Run, Blackwater Creek and the Little Wekiva River), and 30 contributing groundwater springs. The southern-most tributary, the Little Wekiva River, the only main tributary to the Wekiva River that is influenced by the highly developed Orlando area.

The Wekiva River is located within an area of Karst (limestone) geology, where the surface water and groundwater are closely connected. Spring flow from springs in the basin is supplied mostly by the Floridan aquifer, and encompasses approximately 60 percent or more of the total flow within the Wekiva River. Because of this, the river’s water quality and flow expand beyond the surface water drainage basin, or watershed, to also include the larger groundwater basin (springshed). The Little Wekiva River watershed receives drainage from an urbanized 42-square-mile area west and north of downtown Orlando.

With each heavy rain, excessive storm water flows through ditches and canals and into the Little Wekiva River. The storm water erodes the river’s side banks and channel bottom, and deposits sediments and pollutants along the way. Development within the floodplain, excessive stormwater flows, and the buildup of sediments has contributed to frequent flooding in the surrounding residential areas and has deteriorated water quality in the Little Wekiva and Wekiva rivers. Strategies have been developed to maintain the Little Wekiva River as a sustainable resource, including a Basin Management Action Plan (BMAP) for the total maximum daily load (TMDL), erosion control projects, protecting river banks with structures and vegetation, sedimentation control, etc.