District modelers help track down the keys to protecting Florida’s water

In this fast-paced, digital age when volumes of information are available almost instantly through the touch of a computer screen, the work of modelers at the St. Johns River Water Management District is sometimes more like the work of famed fictional detective Sherlock Holmes — slow, methodical yet extremely effective.

Combining the two approaches — old fashioned detective work with today’s most advanced technology — the modelers’ work has far-reaching benefits and impacts for the district and the public.

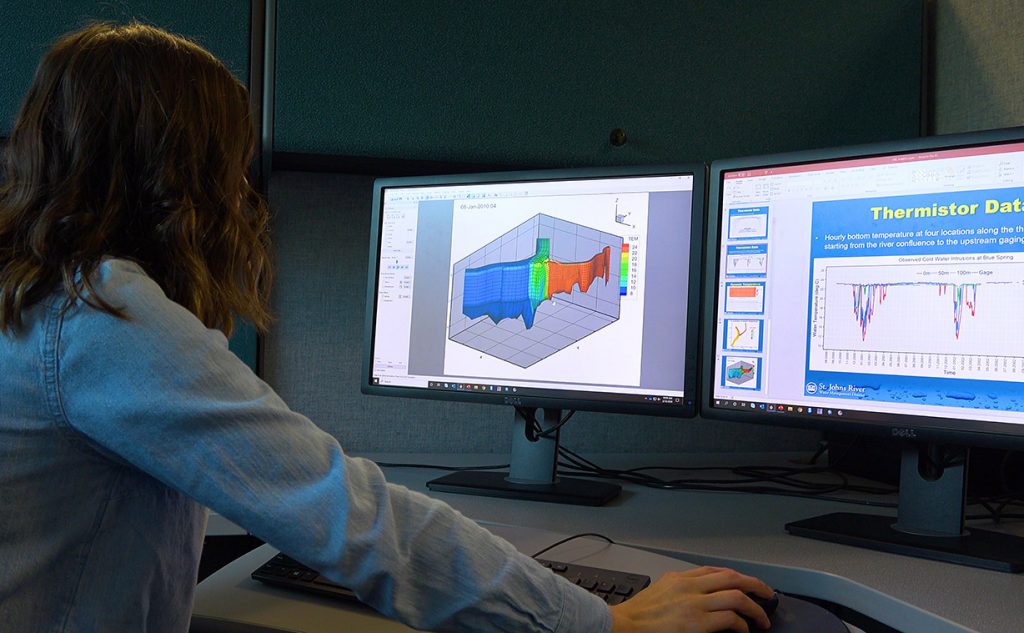

Computer-generated models tell scientists a lot about water above and below the ground, what water has done in the past and helps provide insight into what it might do in the future. These models are used extensively in the district’s regulatory work, to help determine minimum flows and levels for water bodies, to warn about and alter potentially negative impacts from project construction and for water supply planning. Modeling is a long, complicated process, and one that staff ensure is done with rigorous quality assurance checks.

“The approaches and assumptions that the district uses in its modeling work encompass a robust effort. It’s very complicated,” says Dr. Sherry Brandt-Williams, bureau chief for the district’s Bureau of Watershed Management and Modeling, a 15-year veteran of the district.

When modeling work is requested, the district’s team of experts in the fields of geology, engineering, hydraulics, hydrology and ecohydrology first look at what question needs to be answered. Whether the district is working on a long-term water supply planning modeling effort that is partially based on historic rainfall or river and stream levels, or a regulatory limit to determine how much groundwater is available in a certain area, like good detectives these modelers must first understand the real problem to determine what information and assumptions need to be included and analyzed to reach an accurate answer.

Among the district’s super sleuths is Dr. Peter Sucsy, a Technical Program Manager with 27 years of experience at the district. He was part of the team that worked with state and national experts in 2012 to develop the models and analyses for the district’s nationally recognized Water Supply Impact Study, the most comprehensive and scientifically rigorous analysis of the St. Johns River ever conducted.

Sucsy says, “My job requires a lot of custom programming. There is no escape from writing, testing and optimizing code.” And while that may sound tedious, it’s part of the detective work he loves. “I really enjoy building a model of a water body and watching it come to life. It never ceases to amaze me when standing on the shore of the St. Johns River that our models really simulate the details of its motions.”

To get a model to the level that it comes to life takes lots of data. That’s where the district’s Bureau of Water Resource Information team comes in. From more than 1,600 monitoring stations throughout the district’s 18-county region, staff collect, process, verify and store more than 16 million bits of data annually about rainfall, groundwater and surface water.

Modelers use new and historical data, compare the data against known factors to ensure accuracy, obtain peer review by outside experts, and simulate model runs to provide an answer. So much data and computing time is needed that each step could take three to six months to complete. Massive amounts of mathematical computations are processed to reach an answer (sometimes 30 to 50 equations for each time increment in the simulation; for example, multiply 24 solutions to 30 equations each day for several years. That’s a lot of calculations).

“Modeling work is data intensive and also time intensive,” Brandt-Williams says. “Even so, all the effort that goes into them is important because models help us understand future water needs.”

Models can be statistical or perception based. The district uses a combination of mechanistic and statistical models. Statistical models tell scientists what happened. Mechanistic models tell scientists what could happen.

While the district’s staff does not build a model from scratch, they do need to understand the principles behind each equation in the model to ensure the right data are used. They enter huge volumes of information in already rigorously tested and proven models to customize each model for northeast and east-central Florida’s unique environmental and geological features. When staff are assured a model is ready to provide an answer for the question, it takes computers anywhere from a few minutes to several days to provide that answer, and many iterations are required after that to make sure simulations closely match observed conditions and provide a reasonable result.

Bureau Chief Brandt-Williams says, “You’ve heard the phrase ‘garbage in, garbage out.’ We don’t want garbage, so staff make sure there are no glitches in the data and the input process. They calibrate against known information to make sure the new model run is accurate based on information they already know to be true.”

Groundwater modeling is a different kind of complexity than surface water modeling because of the limited availability of subsurface geologic data, says Lanie Meridth, a hydrologist who began fulltime work with the district in 2016 after a stint as a district intern.

Brandt-Williams agrees. “Groundwater modeling uses assumptions and interpretation between the gaps in the data points we have,” she says. “What lies beneath the land’s surface has not been extensively mapped like aboveground. It’s not like looking at a Google Earth map.”

I enjoy being able to develop and improve tools and programs that are used to analyze model results to answer a wide range of scientific questions

As one of the newer members of the modeling detective team, Meridth undertook a major project early in her district career, designing a modeling database that combines hydrologic, geospatial, hydrodynamic and water quality models with data spanning a 10-year period. She created and organized processes for obtaining and quality-assuring these data, providing staff across the district access to the model boundaries and associated information all in one easy location.

“I enjoy being able to develop and improve tools and programs that are used to analyze model results to answer a wide range of scientific questions,” Meridth says. “The answers to these questions are used to support water resource decisions, so I feel that my work serves an important purpose at the district.”

Important, indeed, as these modeling detectives solve another mystery. And like Sherlock Holmes, they are ready to rise to the next challenge.